Much excitement over a recent article by The Guardian’s medical journalist, Dr Luisa Dillner, in which she canvasses the views of a physiotherapist, an osteopath and a ballet teacher on the vexed topic of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ posture, with a special focus on the latter’s effects on health and well-being.

There were several strands to the argument but the main theme was that so-called bad posture – ‘usually defined as slumping, leaning forwards or standing with a protruding belly’ – is not the primary reason why so many people in the UK experience chronic lower back pain.

This is not a new argument. As I explain in my book, Alexander Technique in Everyday Activity: Improve how you sit, stand, walk, work and run, the reasons why people develop chronic lower back problems are multiple and complex:

‘Although the precise cause of chronic back pain is often difficult to pinpoint, it is usually related to conditions such as herniated disc – the so-called slipped disc – and by a variety of inflammatory processes in the musculoskeletal system, as well as age-related degeneration, especially in those over 65.’

I also highlight that lower back pain is linked to anxiety and stress.

And in my book, I offer some advice to those suffering from chronic lower back pain – namely, that it is very important to obtain an accurate medical diagnosis in order to rule out any existing medically treatable pathological problem of the spine.

Interestingly, the physiotherapist and osteopath interviewed by Dr Dillner did concede that once someone has developed chronic lower back pain ‘posture may affect it’ and that ‘sitting for a long time’ is best avoided.

But what wasn’t mentioned in The Guardian article (though it is covered in my book) concerns an important discovery made in 2006 by a team of Canadian and Scottish scientists.

It is that how we sit on a chair has enormous implications for spinal health. The team, which used an innovative whole-body MRI scanner to investigate 22 adult volunteers with ‘healthy backs’, found at the start of the study that despite being asymptomatic 12 of the group exhibited a significant degree of disc degeneration or disc protrusion.

The scans then revealed that sitting on a chair with feet touching the floor in either a forward slouch or an upright 90 degrees, ‘good posture’ position, had a significant impact on the vertebral column, since the lower spinal discs in particular were already showing signs of deformity.

In fact, this effect was greatest when subjects adopted the sit up ‘straight’ position. In as little as 10 minutes fluid was leaking out of the inner core of the discs. This finding is highly significant, considering that the 23 sponge-like intervertebral discs constitute around one third of the total length of the spine, and play a critical role as shock absorbers in everyday movement, especially in bending and twisting motions.

From an Alexander Technique point of view sitting up ‘straight’, as most people in our culture understand it, is in fact over-straight. Simply put, it’s just another way of tightening the neck, raising the chest and hollowing the back. In turn, that misuse lifts the sitting bones from the chair and transfers body weight on to the thighs, creating inappropriate downward pressure along the spinal column, including the discs. The alternative of slumping isn’t much better.

Instead, in order to sit upright painlessly and efficiently we need to learn the skill of giving our weight to our ischial tuberosities – the sitting bones at the base of the spine.

Only then can our anti-gravity and non-tiring support muscles transfer the weight of our head, upper body and arms into whatever support surface is available. This could be the ground itself, or a raised surface such as a chair, tree stump or rock, or moving surface such as a horse, elephant or camel.

To make this clearer you can try this experiment. Locate your sitting bones by sitting on a flat surface, such as a wooden chair, and put the palm of each hand under each buttock. Through the skin, fatty tissue and thick muscle you will feel a bony protrusion under each hand. At this point let yourself slump so that your spine assumes a C-shaped curve. You will notice how you roll on to the back edge of your sitting bones and your weight transfers on to the rear of the pelvis and towards the tailbone (coccyx).

Now try sitting up ‘straight’. Chances are that you are now arching your back. If so, you will experience how your support contact moves on to the very front edge of your sitting bones, in such a way that much of your weight is taken by your thighs.

By contrast, see if you can find a way of sitting in balance so that your weight is taken more or less by the middle of the curved arch of your sitting bones, with your double S-shaped spine extending upwards and your head freely poised on top of it.

This is balanced sitting. It’s easier said than done, of course. But it’s the only way to sit to avoid exacerbating chronic lower back pain, while also preserving the long-term integrity of the discs of your spine.

You can read more about an Alexander approach to sitting and other movements in Seán Carey’s Alexander Technique in Everyday Activity: Improve how you sit, stand, walk, work and run

Available through Amazon with free P & P

xander told Marjory Barlow and the other students on his first training course group that once they had qualified as teachers they would find wall work very useful to perform in the intervals between lessons, especially if there wasn’t sufficient time to lie down on the floor or table. One reason why wall work is so valuable, FM went on to explain, derives from the sensory feedback that becomes available by lightly placing the whole of one’s back against a firm surface, such as a smooth wall or door, head freely poised on top of the spine and, then, using inhibition and direction, to make one or more carefully-thought-out movements.

xander told Marjory Barlow and the other students on his first training course group that once they had qualified as teachers they would find wall work very useful to perform in the intervals between lessons, especially if there wasn’t sufficient time to lie down on the floor or table. One reason why wall work is so valuable, FM went on to explain, derives from the sensory feedback that becomes available by lightly placing the whole of one’s back against a firm surface, such as a smooth wall or door, head freely poised on top of the spine and, then, using inhibition and direction, to make one or more carefully-thought-out movements.

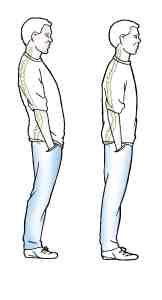

FM Alexander famously said that improved coordination comes ‘from the head downwards’. Does that mean that he neglected other parts of the body, including the feet? Definitely not. He knew from observing himself using a three-way mirror arrangement that while standing (and in motion) that as well as interfering with the balance of his head on his neck he was also making unnecessary muscular tension in his feet. In fact, he was contracting and bending his toes downwards in such a way that he was throwing his weight onto the outside of his feet, creating an arching effect, which in turn interfered with his overall balance.

FM Alexander famously said that improved coordination comes ‘from the head downwards’. Does that mean that he neglected other parts of the body, including the feet? Definitely not. He knew from observing himself using a three-way mirror arrangement that while standing (and in motion) that as well as interfering with the balance of his head on his neck he was also making unnecessary muscular tension in his feet. In fact, he was contracting and bending his toes downwards in such a way that he was throwing his weight onto the outside of his feet, creating an arching effect, which in turn interfered with his overall balance.