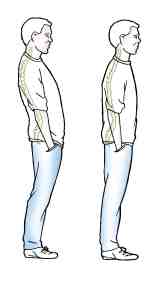

In this exclusive excerpt from his new book Exploring the Alexander Technique with Walter Carrington: Lessons and Games, Seán Carey reveals how mastering semiflexion, a simple bend of the ankles, knees and hips, can unlock effortless movement, create better balance and facilitate an energising release in tension.

Learning to acquire competence in semiflexion often requires sustained hands-on assistance from a teacher to maintain proper form and prevent the triggering of ingrained habits.

On the other hand, if performed correctly, semiflexion represents a dynamic position of mechanical advantage. As you descend from a fully upright position to an intermediate or even a deep squat, there will be a beneficial redistribution of muscle tension. At the same time, your rib cage contracts and expands elastically and your feet open onto the ground.

When you return to upright from semiflexion, you may experience a powerful release and noticeably improved muscle tone. The dynamism of this attitude has been created by the antagonistic muscular actions of the body parts releasing in opposite directions – ‘head forward, knees forward, hips back, one against the other’ – as Alexander, by way of encouragement, often said.

Each day of the training course Walter offered hands-on work to all students and teachers, which usually involved chair work, but during some sessions he showed me different ways of moving into and out of semiflexion.

On one occasion he stood to my left and used his hands to help me find a better balance. As my neck column released upward, my back opened out, and my feet released onto the ground, he instructed me to direct my head forwards and up, saying, ‘Don’t do anything, just think it’, and guided me into semiflexion.

Walter then told me to think of releasing my ankles even more so that my shins ‘fell up and forwards’, while directing my thighs ‘back and up’ or towards my pelvis. Still in semiflexion I was also asked to direct my torso to follow the lead of my head.

On another occasion Walter emphasised the importance of lengthening and widening the torso to perform semiflexion. He had me stand behind him and place my hands on either side of his rib cage.

Next, Walter moved into the position of mechanical advantage by bending his ankles, knees and hips. I could feel with my hands that he was not sinking into his legs because he was maintaining the lengthening of his spine and the widening of his back.

Walter then guided me through the movement. As I stood, he placed his hands on my rib cage and asked me to direct my back ‘back and up’ as he took me slightly up and back from my ankles. Because my back was elastically releasing this made it very easy to bend my ankles, knees and hips.

To exit semiflexion Walter gave me two options. First, he recommended thinking of my head moving back to its full height, which would cause my legs to straighten without any clenching or pushing required. Alternatively, he steered my hips back and down, explaining that allowing the tail to drop slightly would cause my head to rise, much like a seesaw. As a result of this guided movement, I discovered I could move my head away from my heels to stand upright without using unnecessary muscular effort.

However, there are other effective ways to transition from semiflexed to upright that you can play around with. For instance, if your back muscles are properly engaged, you can walk forward without wobbling and gradually, without stiffening your neck, lifting your chest or pulling your back in, come upright. You can also walk backwards, directing your back back and then gradually return to a vertical attitude.

Seán Carey’s book, Exploring the Alexander Technique with Walter Carrington, is now available. This exclusive hardback book offers practitioners an insider’s perspective into Walter Carrington’s profound teachings and approach.

Order your copy of this limited edition today via the HITE website or Amazon.

FM Alexander famously said that improved coordination comes ‘from the head downwards’. Does that mean that he neglected other parts of the body, including the feet? Definitely not. He knew from observing himself using a three-way mirror arrangement that while standing (and in motion) that as well as interfering with the balance of his head on his neck he was also making unnecessary muscular tension in his feet. In fact, he was contracting and bending his toes downwards in such a way that he was throwing his weight onto the outside of his feet, creating an arching effect, which in turn interfered with his overall balance.

FM Alexander famously said that improved coordination comes ‘from the head downwards’. Does that mean that he neglected other parts of the body, including the feet? Definitely not. He knew from observing himself using a three-way mirror arrangement that while standing (and in motion) that as well as interfering with the balance of his head on his neck he was also making unnecessary muscular tension in his feet. In fact, he was contracting and bending his toes downwards in such a way that he was throwing his weight onto the outside of his feet, creating an arching effect, which in turn interfered with his overall balance.

The flat, fan-like latissimus dorsi muscles are part of a group of what anatomists term “superficial muscles” – that is, they are to be found just under your skin. In fact, you can easily locate part of one or other latissimus dorsi muscle by using your fingers and thumb to pinch the widest part of your back behind your armpit.

The flat, fan-like latissimus dorsi muscles are part of a group of what anatomists term “superficial muscles” – that is, they are to be found just under your skin. In fact, you can easily locate part of one or other latissimus dorsi muscle by using your fingers and thumb to pinch the widest part of your back behind your armpit.