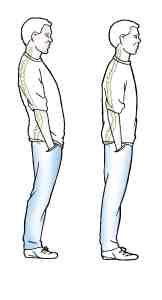

FM Ale xander told Marjory Barlow and the other students on his first training course group that once they had qualified as teachers they would find wall work very useful to perform in the intervals between lessons, especially if there wasn’t sufficient time to lie down on the floor or table. One reason why wall work is so valuable, FM went on to explain, derives from the sensory feedback that becomes available by lightly placing the whole of one’s back against a firm surface, such as a smooth wall or door, head freely poised on top of the spine and, then, using inhibition and direction, to make one or more carefully-thought-out movements.

xander told Marjory Barlow and the other students on his first training course group that once they had qualified as teachers they would find wall work very useful to perform in the intervals between lessons, especially if there wasn’t sufficient time to lie down on the floor or table. One reason why wall work is so valuable, FM went on to explain, derives from the sensory feedback that becomes available by lightly placing the whole of one’s back against a firm surface, such as a smooth wall or door, head freely poised on top of the spine and, then, using inhibition and direction, to make one or more carefully-thought-out movements.

Going on to the toes is one such movement. With your head leading, slide your body upwards (in stages if necessary) – ‘take plenty of time,’ Marjory advised me when I performed the movement in her teaching room – so that you go on to the balls of your feet and then your toes, without pressing back against the contact surface or bracing back your knees or holding your breath. Having arrived on tiptoe, it’s a good idea to pause at this juncture and release any unnecessary holding or excess tension in the buttocks, lower back, knees and ankle joints made while moving upwards. (When first performing the activity most of us will find that there’s often quite a lot of tension to discard. But definitely one way you can help the process along is by directing your heels to release away from your sitting bones or hip joints.) To return to the floor maintain your light contact with the wall or door and allow your ankles to release very slowly so that you maintain your internal length.

You now have the task of coming away from the wall without using some sort of leverage – for instance, by not succumbing to the desire to push with one or both of your buttocks or employing a quick flick of your shoulder blade. That, of course, is easier said than done – a true test of inhibition and direction.

You can read more about Marjory Barlow’s Alexander teaching techniques in Seán Carey’s new book, ‘Think More, Do Less: Improving your teaching and learning of the Alexander Technique with Marjory Barlow’, which has been written for Alexander teachers, trainees and advanced students. It is now available through Amazon or HITE.

FM Alexander famously said that improved coordination comes ‘from the head downwards’. Does that mean that he neglected other parts of the body, including the feet? Definitely not. He knew from observing himself using a three-way mirror arrangement that while standing (and in motion) that as well as interfering with the balance of his head on his neck he was also making unnecessary muscular tension in his feet. In fact, he was contracting and bending his toes downwards in such a way that he was throwing his weight onto the outside of his feet, creating an arching effect, which in turn interfered with his overall balance.

FM Alexander famously said that improved coordination comes ‘from the head downwards’. Does that mean that he neglected other parts of the body, including the feet? Definitely not. He knew from observing himself using a three-way mirror arrangement that while standing (and in motion) that as well as interfering with the balance of his head on his neck he was also making unnecessary muscular tension in his feet. In fact, he was contracting and bending his toes downwards in such a way that he was throwing his weight onto the outside of his feet, creating an arching effect, which in turn interfered with his overall balance. The flat, fan-like latissimus dorsi muscles are part of a group of what anatomists term “superficial muscles” – that is, they are to be found just under your skin. In fact, you can easily locate part of one or other latissimus dorsi muscle by using your fingers and thumb to pinch the widest part of your back behind your armpit.

The flat, fan-like latissimus dorsi muscles are part of a group of what anatomists term “superficial muscles” – that is, they are to be found just under your skin. In fact, you can easily locate part of one or other latissimus dorsi muscle by using your fingers and thumb to pinch the widest part of your back behind your armpit.