Last week it was the effect on the feet of wearing high heels that was in the news. This week it’s whether running wearing a pair of trainers is better for you than running barefoot. University of Queensland researchers found that the cushioning and arch support features found in most modern trainers and running shoes can potentially impair ‘foot-spring function’– though with the important caveat that shod running may contribute to other advantages in a runner’s foot muscle function, especially in the activation of the muscles along the longitudinal arch of the foot. The researchers concluded (as researchers tend to do) that more research was required to explore the relationship between the foot and the muscles around the ankle and knee joints during running.

Certainly, all the top athletes I’ve observed in recent years wear some sort of shoe when competing. On the other hand, many elite middle and long-distance runners, hailing from rural areas in countries such as Kenya and Ethiopia, have grown up not wearing shoes or only wearing them occasionally. In fact, there is a huge advantage for all of us at least to walk barefoot whenever possible. Why? Well, the sensory nerves on the bottom of your feet provide important proprioceptive information about the ground you are walking on. Your brain and the rest of your nervous system interpret these signals to keep you upright with the minimum amount of effort in locomotion. This process is made more difficult if shoes are worn – and interestingly the more cushioned or stiffer the shoes, the worse the problem. In fact, even wearing socks on your feet interferes with this proprioceptive process.

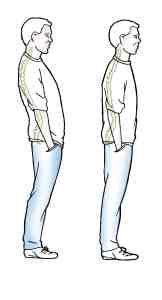

However, walking barefoot and running barefoot are not equivalent activities. Most experts, such as Harvard evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman, recommend that if you are used to running with shoes but wish to make the change to running barefoot or using minimalist shoes you allow plenty of time to make the transition. And, from an Alexander Technique perspective, it’s not just your feet that you need to be concerned with. Much more important in many ways is the balance of your head on your neck. You want to keep your head freely poised so that your back musculature provides the necessary support for your body weight and allows your legs to move freely. Tighten your neck muscles and you’re pulling your head down on to your shoulders and compressing your whole body from the crown of your head to the soles of your feet. In short, you will run heavy and feel heavy. And that’s true whether your feet are shod or not.

For more information on walking and running read Seán Carey’s Alexander Technique in Everyday Activity: Improve how you sit, stand, walk, work and run

Available through Amazon with free P & P

The flat, fan-like latissimus dorsi muscles are part of a group of what anatomists term “superficial muscles” – that is, they are to be found just under your skin. In fact, you can easily locate part of one or other latissimus dorsi muscle by using your fingers and thumb to pinch the widest part of your back behind your armpit.

The flat, fan-like latissimus dorsi muscles are part of a group of what anatomists term “superficial muscles” – that is, they are to be found just under your skin. In fact, you can easily locate part of one or other latissimus dorsi muscle by using your fingers and thumb to pinch the widest part of your back behind your armpit.